Lightpanda Now Supports robots.txt

Muki Kiboigo

Software Engineer

TL;DR

We shipped robots.txt support into Lightpanda’s main branch. When you pass --obey_robots, the browser fetches and parses the robots.txt file for every domain it touches before making any requests. The implementation fetches once per root domain and manages a cache per session.

Why This Matters for Machine Traffic

robots.txt is a plain text file that lives at the root of a domain, typically at /robots.txt. It describes which paths a crawler should and shouldn’t access, and for which user agents those rules apply. The format has been around for a while and is also known as RFC 9309 .

A typical file looks like:

User-agent: *

Disallow: /private/

Allow: /public/

User-agent: Googlebot

Allow: /The key thing to understand is that robots.txt is not a security mechanism. It requires clients to be good web citizens and to respect the intentions of the site owner. Google honors it, and so do most reputable crawlers.

The volume of machine-generated web traffic has grown substantially and a meaningful portion of it ignores the conventions that made large-scale crawling sustainable in the first place. Sites are spending meaningful resources dealing with bot traffic they never consented to.

Our Position

Lightpanda is a browser for machines and we want it to be the default infrastructure for AI agents, scrapers, and automation pipelines. That goal only makes sense if machine traffic becomes a better citizen of the web.

We built robots.txt support because we think it should be easy to do the right thing. That said, we are not the end user here. Lightpanda is a tool, and like any browser, what you do with it is your responsibility.The feature is currently opt-in via --obey_robots.

If you’re building a product that crawls third-party websites, respecting robots.txt is good practice. It reduces the chance your traffic gets rate-limited or blocked and it’s the kind of behavior that keeps the web functional for everyone.

Parsing a Robots File

We implemented our own Robots parser, living in src/browser/Robots.zig. It follows the rules set out in RFC 9309 , ensuring that we capture all of the rules that apply to our User-Agent.

The parser handles the standard robots.txt directives: User-agent, Allow, and Disallow.

User-Agent matching uses case-insensitive comparison, ensuring that Lightpanda, lightpanda, and LIGHTPANDA all match the same rule block.

For path matching, the implementation handles the * wildcard and the $ end-of-path anchor that the RFC defines. These are quite important and are used extensively in the real world.

The Singleflight Problem

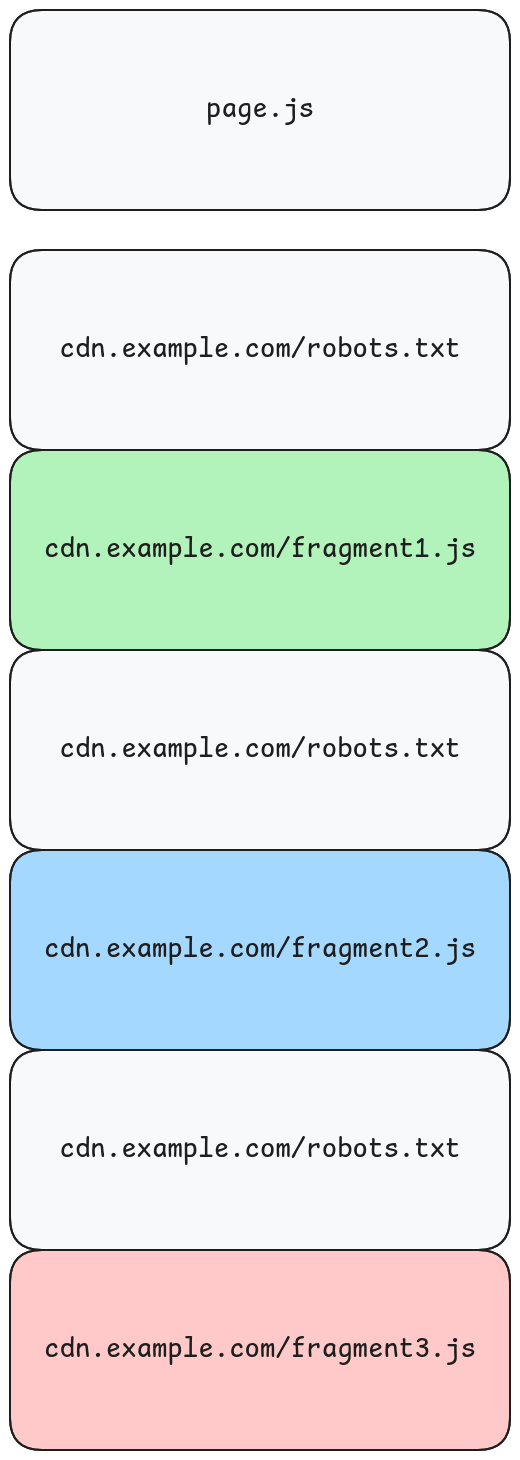

One important thing to consider is the behavior when a page loads resources from the same domain concurrently.

Consider a script, page.js, that fetches 3 additional JavaScript files from cdn.example.com. Without any coordination, the browser would fire off 3 separate requests for cdn.example.com/robots.txt before any of those JavaScript requests would proceed. On a real world page, this would lead to many redundant requests.

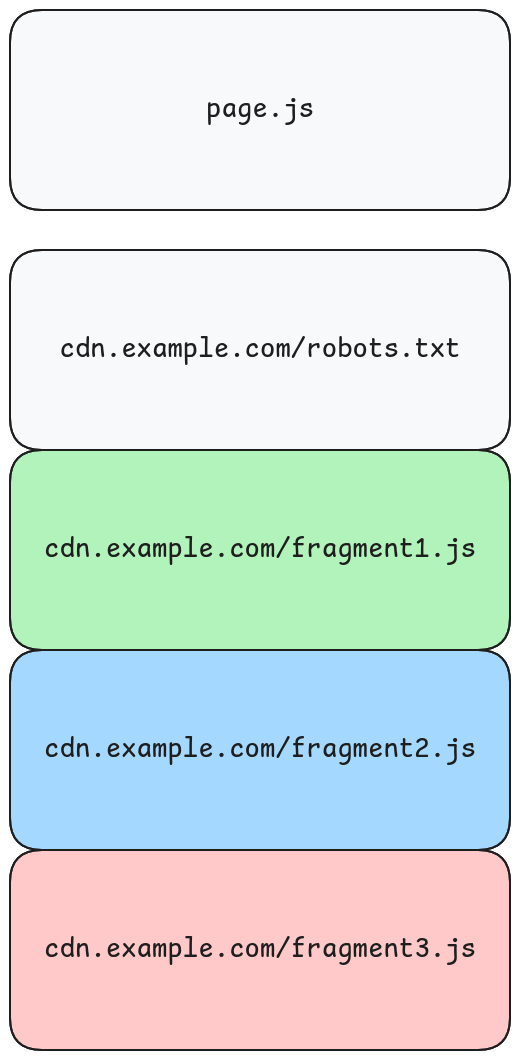

The solution is to make one request to the cdn.example.com/robots.txt and queue all of the additional requests after it. This way, we only fetch and parse the robots.txt once and amortize that cost across all of the subsequent requests.

The first request to a domain that needs robots.txt kicks off the robots fetch and registers the actual request in a queue keyed by robots URL.

- Subsequent requests to the same domain while

robots.txtis still in flight add themselves to that queue instead of firing a new robots fetch. - When the

robots.txtresponse arrives, the browser parses and caches the result into aRobotsStoreto be shared across the session. - The browser checks all of the queued requests, fetching their resources if they are allowed or blocking them if they are disallowed.

This means you only ever fetch cdn.example.com/robots.txt once per session, regardless of how many resources come from that domain.

Internally, the queue is stored in the HTTP client as pending_robots_queue, a hash map from robots URL to a list of pending requests. When we finish fetching the robots.txt file, the callback drains the queue:

if (allowed) {

for (queued.items) |req| {

ctx.client.processRequest(req) catch |e| {

req.error_callback(req.ctx, e);

};

}

} else {

for (queued.items) |req| {

log.warn(.http, "blocked by robots", .{ .url = req.url });

req.error_callback(req.ctx, error.RobotsBlocked);

}

}Blocked requests get a RobotsBlocked error that propagates up through the same callback chain as any other HTTP error.

Checking Every Domain

If you’re using --obey_robots, you’re explicitly signaling that you want to behave like a crawler. Crawlers check robots.txt for every domain they fetch resources from. RFC 9309 doesn’t carve out an exception for subresources. This means that all requests are checked against the robots.txt of their domain.

Google’s own robots.txt documentation shows examples where site owners explicitly configure rules for CSS and JS files, highlighting the expected behavior of subresources being governed.

How to Use It

If you’re running Lightpanda locally:

lightpanda serve --obey_robotsWhen --obey_robots is set, every HTTP request goes through the check before it’s made. Requests to domains that disallow your user-agent get blocked with a log warning. Requests to domains with no robots.txt, or robots.txt that permits access, proceed normally.

The user-agent Lightpanda/1.0 is what the robots.txt rules match against, but use the --user_agent_suffix option to append your own identity.

What’s Next

We’re thinking about exposing robots.txt check results through the CDP interface, so automation clients can inspect why a request was blocked rather than just seeing an error.

If you’re building on top of Lightpanda and have opinions about how robots.txt handling should work in your use case, we’d like to hear from you.

You can see the full implementation in PR #1407 and explore the source at github.com/lightpanda-io/browser .

FAQ

What is robots.txt?

robots.txt is a text file at the root of a domain that tells crawlers which paths they should and shouldn’t access. It’s a convention, not a security mechanism. Crawlers that honor it check the file before making requests.

Why is robots.txt support opt-in?

Lightpanda is a tool. Like any browser, what you do with it is your responsibility. We don’t enforce robots.txt compliance by default. The --obey_robots flag lets you choose to respect it when that’s appropriate for your use case.

Does Lightpanda check robots.txt for subresources?

Yes. When --obey_robots is enabled, Lightpanda checks robots.txt for every domain it fetches resources from, not just the origin. This matches how crawlers behave and follows RFC 9309 .

How does the singleflight cache work?

When multiple requests need robots.txt from the same domain, the first request fetches it and subsequent requests queue behind it. When the fetch completes, all queued requests are evaluated at once. You only fetch each robots.txt file once per session.

What happens when a request is blocked by robots.txt?

The request fails with a RobotsBlocked error and a warning is logged. The error propagates through the same callback chain as other HTTP errors, so your automation scripts can handle it.

Can I configure which domains to check?

Currently --obey_robots applies to all domains. We may add finer-grained control in the future. If you have specific requirements, let us know.

Does this affect performance?

There is a performance impact from making an additional request but the singleflight pattern and the session cache minimizes the performance impact, making only one request per domain we encounter.

Muki Kiboigo

Software Engineer

Muki is a computer engineer from Seattle with a background in systems programming. He is the author of open-source Zig projects like zzz, an HTTP web framework, and tardy, an async runtime. He also runs a website at muki.gg. At Lightpanda, he works on the core browser engine.