CDP Under the Hood: A Deep Dive

Pierre Tachoire

Cofounder & CTO

TL;DR

The Chrome DevTools Protocol (CDP) has become the de facto standard for browser automation, but it wasn’t designed for this purpose. Originally built as a debugging and inspection tool, CDP forces modern automation libraries into workarounds. Simple operations like clicking elements or extracting HTML require multiple unnecessary steps because CDP thinks in terms of pixels and rendering, not programmatic control.

Built for Debugging, Not Automation

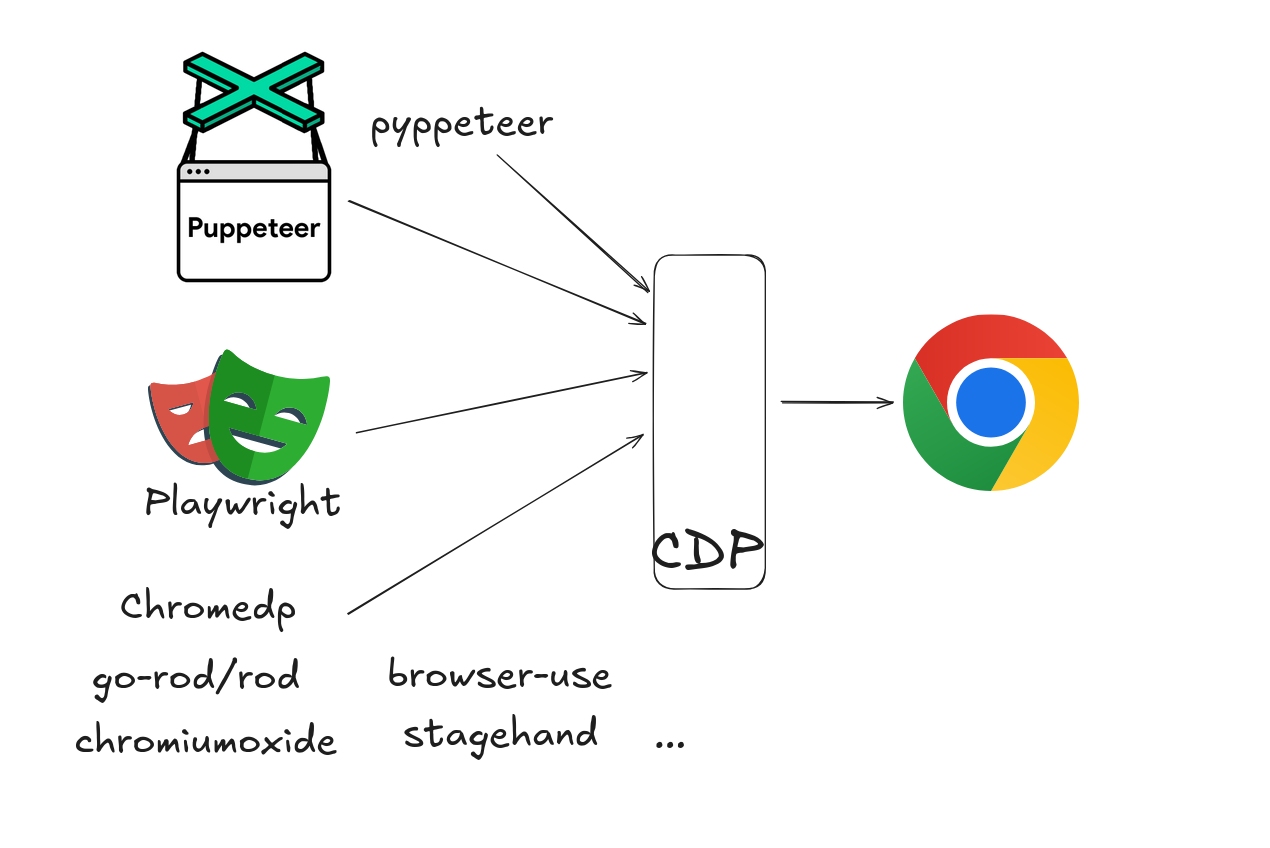

If you’re building automated web applications, you’ve probably worked with Playwright , Puppeteer , or newer tools like Stagehand and Browser Use . These libraries are used for testing, crawling and building web agents. And they’re all built on a protocol that was never meant for automation.

The Chrome DevTools Protocol (CDP) was designed to help developers debug browser behavior, not to control browsers programmatically. This architectural mismatch creates performance bottlenecks, unnecessary complexity, and forces every automation library to reinvent the wheel.

CDP offers 650 commands across 200 types. It gives you deep access to Chrome’s internals. From high level commands like DOM.querySelector, Input.dispatchKeyEvent to low level ones like Runtime.evaluate, Runtime.callFunctionOn.

This flexibility might sound good in theory, but it actually creates a critical problem in practice when you implement the protocol like Lightpanda: there’s no standardized way to do anything. Each automation library interprets CDP differently, leading to unexpected behavior across tools.

The protocol includes domains like:

- Page: For navigating

- DOM: For querying and manipulating the document object model

- Runtime: For evaluating JavaScript in the page context

- Input: For sending user interactions

- Network: For inspecting HTTP requests

- Fetch: For intercepting and modifying HTTP requests

These domains weren’t architected with automation workflows in mind. They were built to support Chrome DevTools, where a human developer clicks through a GUI to inspect elements, set breakpoints, and trace network requests.

Example 1: Four Libraries, Four Ways to Extract HTML

Let’s take a straightforward example: getting the full HTML content of a page. This is basic for every web crawler and testing framework.

The “Pure” CDP Approach

Following CDP’s domain structure, you’d use DOM.getDocument to get the document reference, then DOM.getOuterHTML to extract content. Two calls, clean domain separation. But here’s where theory meets reality.

How Automation Libraries Actually Do It

Every major automation library avoids this approach. Why? Because the DOM domain is computationally expensive and memory-intensive. It was optimized for debugging scenarios where you’re inspecting specific elements, not bulk extraction.

Puppeteer’s Approach

Puppeteer uses Runtime.callFunctionOn to inject JavaScript directly in the page context. It accesses the root element with document.childNodes directly and uses outerHTML for HTML document:

{

"method": "Runtime.callFunctionOn",

"params": {

"functionDeclaration": "() => {

let content = ''

for (const node of document.childNodes) {

switch (node) {

case document.documentElement:

content += document.documentElement.outerHTML;

break;

default:

content += new XMLSerializer().serializeToString(node);

break;

}

}

return content;

}",

"executionContextId": 4,

"returnByValue": true,

"awaitPromise": true

}

}This bypasses the CDP DOM domain entirely.

Playwright’s Approach

Playwright uses a similar plain JavaScript approach with an utility script to run get the documentElement and apply outerHTML.

{

"method": "Runtime.callFunctionOn",

"params": {

"functionDeclaration":

"(utilityScript, ...args) => utilityScript.evaluate(...args)",

"objectId": "5987356902031041503.5.1",

"arguments": [

{"value": "() => {

let retVal = \"\";

if (document.doctype)

retVal = new XMLSerializer().serializeToString(document.doctype);

if (document.documentElement)

retVal += document.documentElement.outerHTML;

return retVal;

}"}

],

"returnByValue": true,

"awaitPromise": true

}

}Chromedp’s Approach

The Go library Chromedp combines a high level DOM.performSearch with the low level Runtime.callFunctionOn:

// First, search for the html element

{

"method": "DOM.performSearch",

"params": {

"query": "html"

}

}

// Then get search results, resolve the node, and call the function

{

"method": "Runtime.callFunctionOn",

"params": {

"functionDeclaration": "function attribute(n) {\n return this[n];\n}\n",

"objectId": "5987356902031041503.2.1",

"arguments": [{"value": "outerHTML"}],

"returnByValue": true

}

}Rod’s Approach

The go-rod/rod library uses a mix of different approaches too, plain JS to retrieve the window and high level DOM.getOuterHTML:

{

"method": "Runtime.callFunctionOn",

"params": {

"functionDeclaration": "() => window",

"objectId": "5987356902031041503.2.8"

}

}

{

"method": "DOM.getOuterHTML",

"params": {

"objectId": "5987356902031041503.2.8"

}

}What They All Have in Common: Nobody Uses the DOM Domain

Following the protocol’s domain structure, the “proper” way to extract HTML would be to use DOM.getDocument followed by DOM.getOuterHTML.

But all four CDP-based libraries avoid the DOM domain for the actual HTML extraction. Puppeteer, Playwright, chromedp, and Rod all ultimately rely on Runtime.evaluate or Runtime.callFunctionOn to execute JavaScript directly in the page context.

This consistent pattern is due to performance.

The DOM domain is computationally heavy and memory-intensive. This isn’t a bug, it’s because the DOM domain was built primarily for debugging scenarios where developers need to inspect element hierarchies, set breakpoints on DOM mutations, and analyze the document structure interactively. It maintains rich metadata and object representations that are invaluable for debugging but unnecessary overhead for automation tasks like extracting HTML.

This GitHub issue on the Puppeteer project illustrates the problem: developers consistently report that DOM domain operations are significantly slower than Runtime-based JavaScript injection for bulk operations.

So while DOM.getDocument would be the more “logical” approach from a protocol design perspective, the reality of production automation has driven every major library toward the same pragmatic solution: inject JavaScript, run it in the browser’s native context, and return the results. It’s faster, uses less memory, and gets the job done.

Example 2: The Coordinate Problem

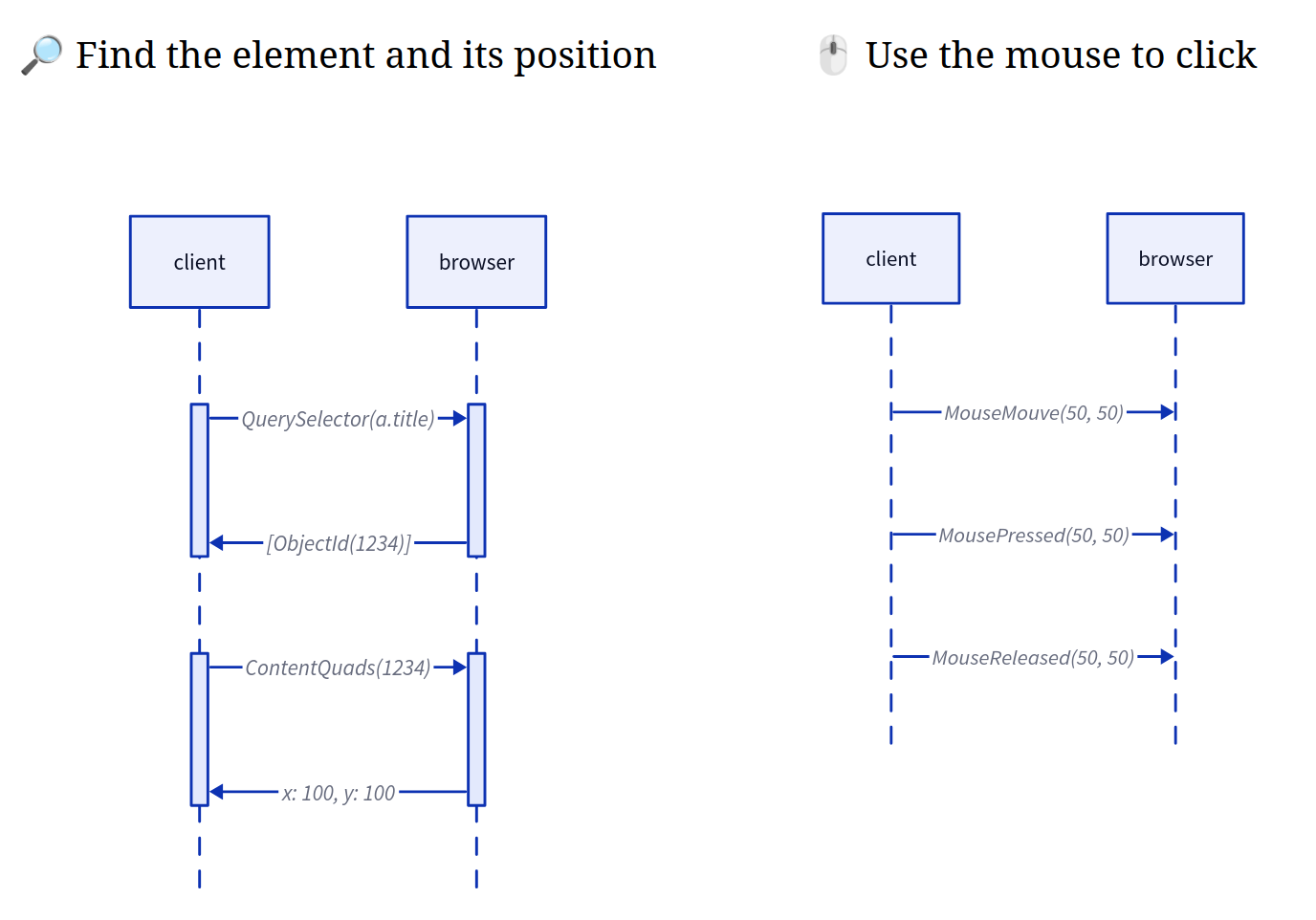

CDP’s rendering-centric approach is apparent if we look at the example of what happens across libraries when you want to click a link:

<h1>

<a class="title" href="/doc/">Documentation</a>

</h1>With Puppeteer:

await page.click('a.title');With Playwright:

await page.locator('a.title').click();This might seem clean, semantic and developer-friendly because you’re telling the browser “click this element” in terms that match how you think about the DOM.

What Actually Happens

DP doesn’t have a command to click an element directly. Instead, every click operation transforms into a three-step coordinate-based process:

- Find the element’s coordinates on the rendered page

- Move the mouse to those coordinates using

Input.dispatchMouseEvent - Dispatch a click event at that location

Why This Architecture Is Wrong for Automation

You wanted to interact with a DOM element, but CDP forced you through the rendering layer.

This creates several problems:

- Unnecessary transformations: Converting from DOM elements to pixel coordinates and back is pure overhead

- Race conditions: The element might move between getting coordinates and clicking

- Viewport dependencies: Coordinates only make sense in the context of the current scroll position

- Multiple round trips: Each step requires a separate network call to the browser

This architecture exists because Chrome was built for humans who need to see pixels on a screen. When you’re debugging, you click where you see things and the rendering engine is the source of truth.

However, we believe that for automation, the DOM is the source of truth and rendering is an implementation detail you shouldn’t need to think about.

Why This Matters for AI and Machine Web Interaction

Modern web automation isn’t just about testing. AI agents are navigating websites to accomplish tasks. Large-scale data extraction systems are processing millions of pages. Browser-based automation is becoming core infrastructure.

These use cases need efficiency and semantic clarity, not debugging tools retrofitted for automation. When your AI agent needs to interact with thousands of pages, it can gain efficiency by removing unnecessary calls back and forth that create friction in machine driven workflows.

How We Handle Coordinates in Lightpanda

Lightpanda doesn’t have a graphical rendering engine calculating pixel positions. But CDP commands expect coordinates, so how do we handle click operations?

Instead of forcing everything through the rendering layer, we use on-demand flat rendering. The automation client can request a flat, semantic representation of the page only when needed, rather than constantly translating between DOM and pixel coordinates.

Here’s how it works:

- When a client requests coordinates for an element for the first time, we add that element to a simple list in our flat renderer

- We return the element’s position in that list as its “coordinates”

- When the client clicks on those coordinates, we look up the element directly in the flat renderer’s list

The coordinates don’t represent the actual pixel position of an element on a rendered page, they’re simply an identifier. The result is we achieve CDP compatibility without needing to rely on graphical rendering:

The Path Forward

The Chrome DevTools Protocol isn’t broken. It’s an excellent debugging tool that does exactly what it was designed to do. But as browser automation evolves from an occasional testing task to core infrastructure, CDP’s limitations become harder to ignore.

The fundamental issue is architectural intent. CDP was built for human developers who need to see, inspect, and understand what’s happening in a browser. Automation needs semantic, programmatic control of the DOM.

The fragmentation across automation libraries isn’t a failure of those tools. It’s a natural consequence of adapting a debugging protocol for automation. Each library makes different tradeoffs because CDP doesn’t provide a clear path forward.

The coordinate-based clicking, the multiple HTML extraction strategies, and the performance overhead aren’t bugs. They’re features of a protocol solving a different problem.

The question isn’t whether CDP works. It does. The question is whether we can build something better when automation is the primary goal from day one.

- Explore Lightpanda’s approach to browser automation

- Try our open-source browser built for machines and AI workflows

- Get in touch and share your experiences with CDP in production

Pierre Tachoire

Cofounder & CTO

Pierre has more than twenty years of software engineering experience, including many years spent dealing with browser quirks, fingerprinting, and scraping performance. He led engineering at BlueBoard with Francis and saw the same issues first hand when building automation on top of traditional browsers. He also runs Clermont'ech, a community where local engineers share ideas and projects.